Radical Incrementalism and the Common Language of Transformation

From small bets to big shifts: why shared meaning powers transformative change.

Establishing a common language with aligned definitions of key terms is an underrated – and essential – challenge in any transformation effort. I was reminded of this last week watching a rich conversation about defining and mapping the concept of “radical incrementalism” as it unfolded among a set of foresight and systems change practitioners.

My initial introduction to the idea of radical incrementalism came about 10 years ago working with John Hagel at Singularity University. John framed radical incrementalism as the strategy of “small bets, smartly made” and aligned toward a bold long-term vision that would be clarified and refined through learning as those small bets paid off – or didn’t. Something of a legend in the consulting world, John had already been writing about radical incrementalism for 15 years in the context of sweeping digital transformation and the “zoom out-zoom in” approach he advocated in his work.

To effectively employ “radical incrementalism” as a strategy, a community or organization has to have a shared understanding that extends far beyond alignment on the common vision – which is no small thing itself. And even with that foundation in place, there needs to be further alignment on what counts as incremental vs. radical, innovation vs. disruption, near-term vs. long-term, etc.

This is quite literally “just semantics,” but it’s also every single thing that depends on those questions of meaning. And that is everything – again, quite literally.

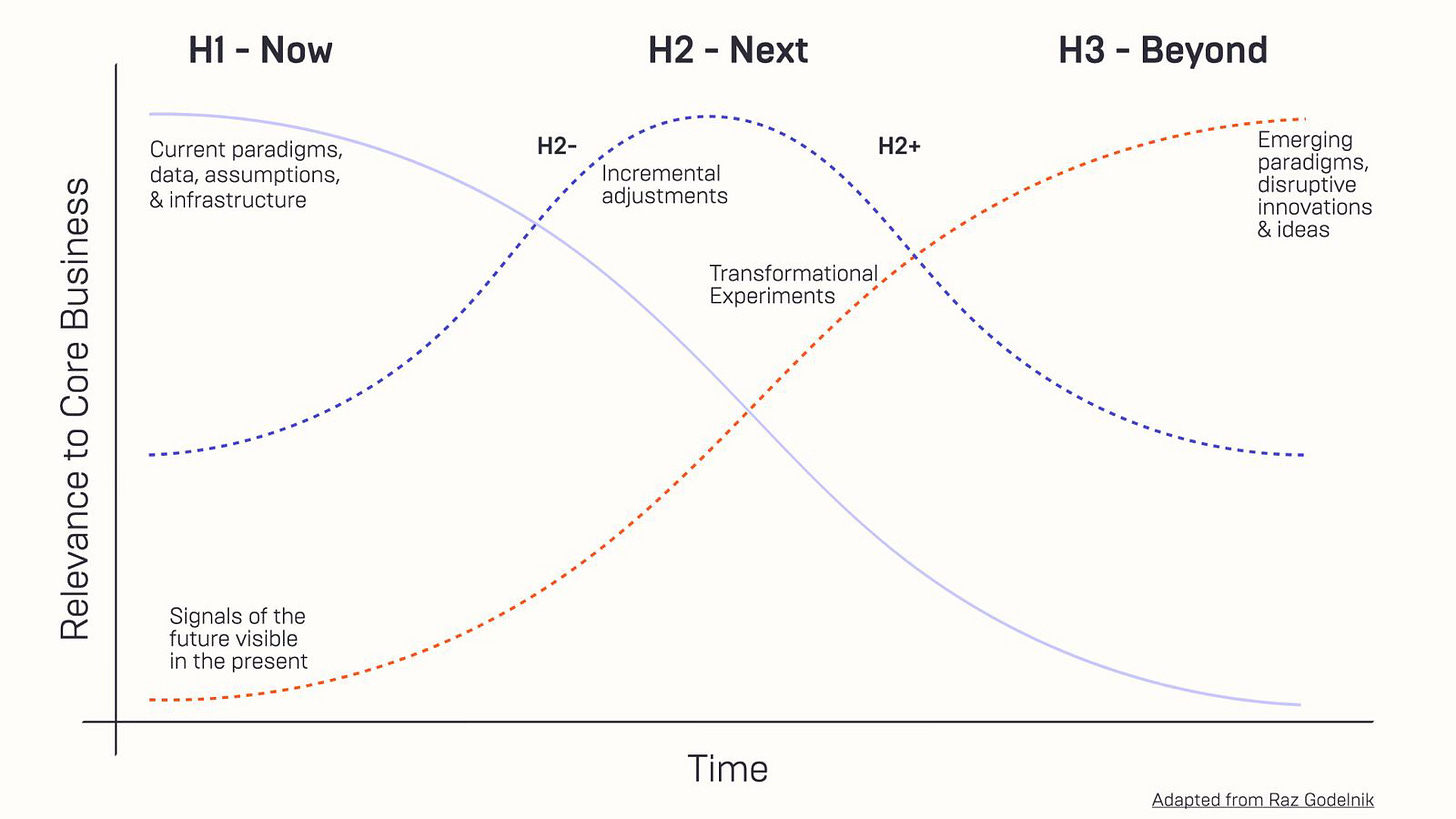

At radical, we often point to the challenge of communicating and strategizing across time horizons as one of the key mindtraps that lead to failed transformation efforts. H1 (“time-horizon 1”) leaders concerned with driving revenue at the core of the business are working with a set of metrics and incentives, a definition of success, and arguably an entire mindset that is — and ought to be — distinct from that of a leader driving projects designed to pay off in H3 (time-horizon 3, aka, the relatively far-off future). These leaders are thinking in and speaking two different languages, and coordination between them requires translation and mutual intelligibility in addition to a shared understanding of the long-term vision.

Conversations help. Sometimes, the difficult ones help the most.

And a simple framework or conceptual map can be incredibly useful as well. We have some of our own (which may be familiar to readers here and are readily accessible in Pascal’s book) for working across time horizons and making sense of core/edge tensions. I also found a visualization that was shared in the “radical incrementalism” discussion I mentioned at the top of this essay to be pretty clarifying, so I’ve reproduced it here with some light adaptation (and welcome any feedback and thoughts, friends!).

The original framework appears in an essay (well worth reading) on the “myth” regenerative business models by the professor and strategist Raz Godelnik, and it charts the relevance/value of H1, H2, H3 initiatives over time – making a key distinction between those targeting H2- and those maturing in H2+ and beyond. The upshot is that initiatives maturing in H2- are likely to be incapable of real transformation of the business – almost by design. They begin too close to the core, and the style of incrementalism they leverage is unlikely to be aligned toward any truly radical outcome in the long term.

The transformative stuff begins in a different place with a different set of conditions established to allow for a radically different trajectory. The incrementalism here isn’t just radical in its outcomes, it’s also radical in its initial requirements: A truly shared vision and a common language to support the process of working toward it.

@Jeffrey

This has significant parallels with necessary approaches for dealing with complex adaptive (dare I say "wicked") challenges, which have come to dominate ever more of the landscape today.

Most challenges under complex contexts do not have the luxury of a silver bullet solution. Think Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety from cybernetics. As Bill McKibben wrote in a 2006 op ed on climate change intervention, "There are no silver bullets, only silver buckshot.”

While classical double-diamond design thinking will converge at single problem and single solution focal points, what many environments actually need is a managed portfolio of experiments, or bets. Each bet offers the opportunity for safe-to-fail learning or building on discovered novelty.

The complexity of managing 100-200 experiments in each context also cannot be centralized with top-down order and a master plan. Rather, they must encourage systems of self-organization and self-governance that are better embedded into the network. So it's a very different mindset. It's also one that Net Zero Cities EU approaches innovation with, for example.