The Future Doesn't Exist. Futures Do.

Why the smartest leaders admit "I don't know" – and plan for multiple tomorrows

Napoleon Bonaparte once defined a military genius as “the man who can do the average thing when all those around him are going crazy.” Given his reputation, one can safely assume that he very much saw himself in this vein.

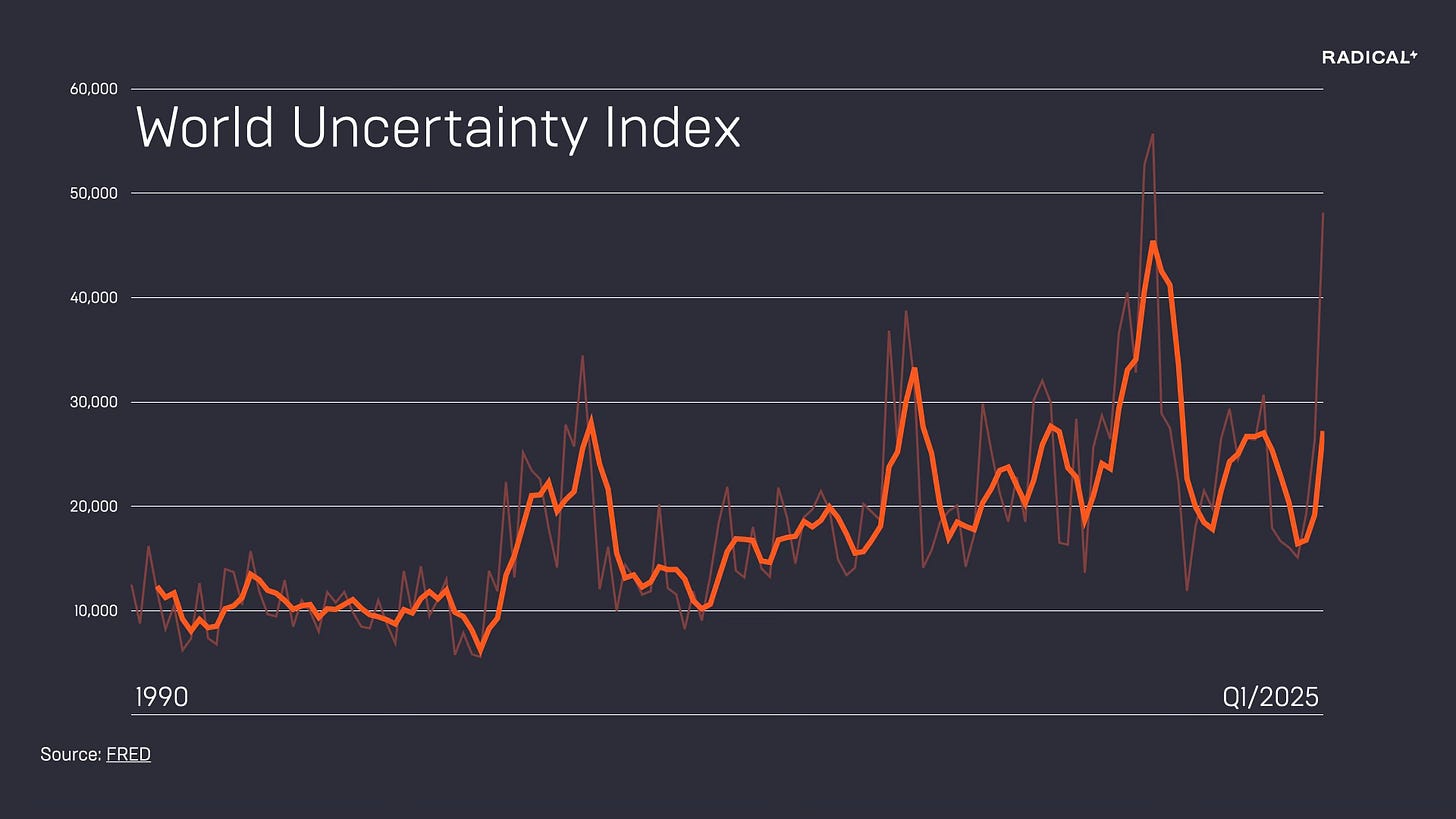

In May 2025, as uncertainty indices spike toward pandemic-era highs and with the April 2nd “Liberation Day” tariffs in play, his definition feels less like military wisdom and more like a survival guide for modern leadership. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) has been publishing its World Uncertainty Index for decades now – it is computed by counting the percent of the word “uncertain” (or its variant) in the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) country reports and, thus, provides a quantification of what we all feel: the world is getting more uncertain on average – and the last few months have been especially trying.

Here is the current visualization:

Uncertainty is nearly back to the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic levels – and this doesn’t include the 2nd quarter of 2025, and therefore before “Liberation Day.”

These uncertainty spikes matter not because of their specific causes – whether tariffs, pandemics, or geopolitical tensions – but because they reveal a deeper challenge: our mental models assume a single, predictable future. “Future” as in: A singular future. “The” future… While English (and pretty much every other spoken language) forces us to speak of “the future” as if it were a single destination, futurists increasingly adopt phrases like “alternative futures” or “future scenarios” to break this linguistic constraint.

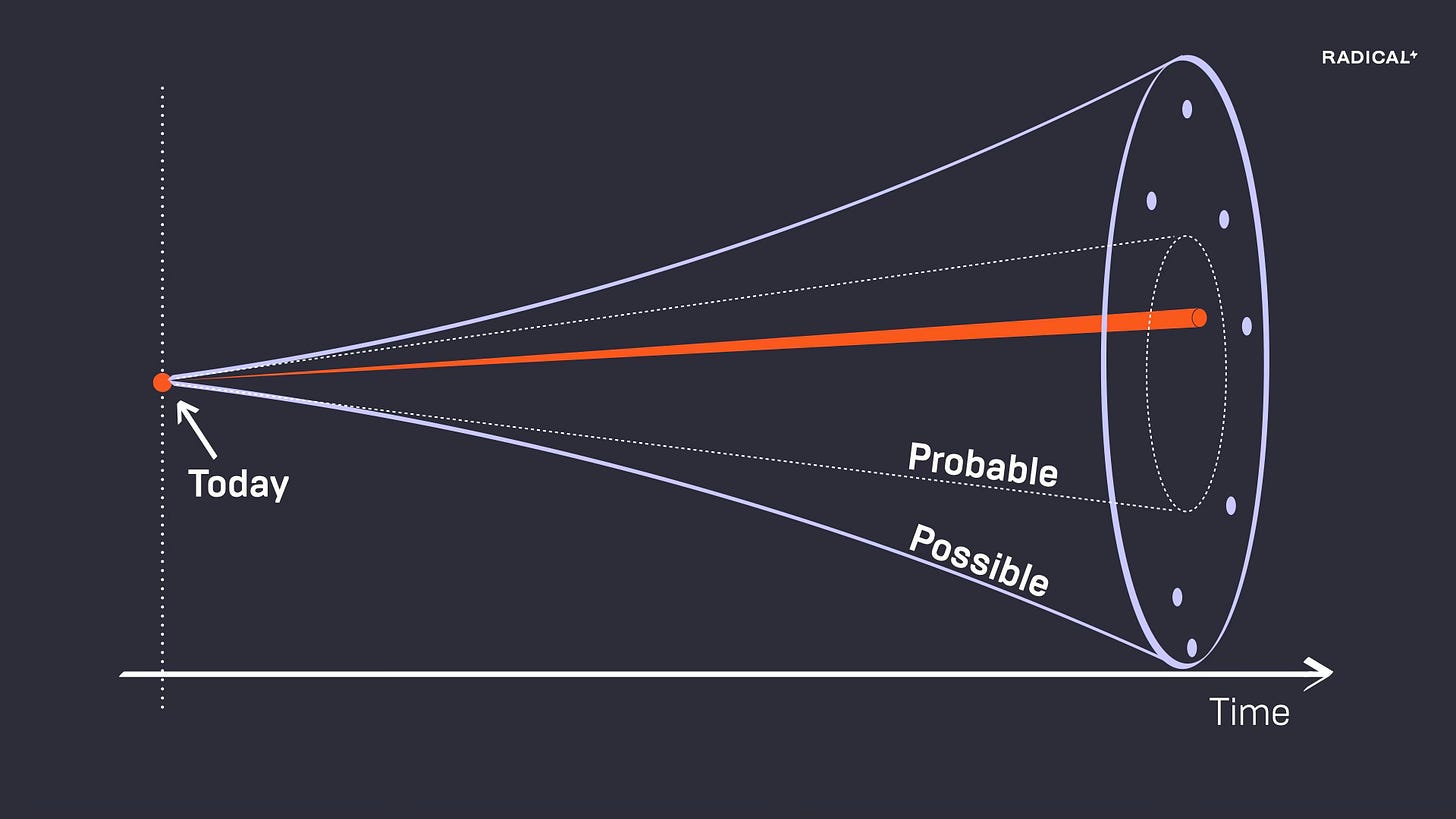

There is the future – a singular occurrence, something Herman Kahn at the RAND Corporation started calling “the official future” (specifically in the context of an organization). But in a world of increasing uncertainty, it is highly debatable if any imagined future is the exact future that will play out – as futurists say, the further out we go into the future, we operate within a widening cone of possible futures, with a smaller subset of probable futures within this cone. Uncertainty expands those cones – it might add to the cone of possible futures, and it certainly widens the cone of probable futures.

Navigating and therefore leading through these uncertainties requires us to first acknowledge that we are, indeed, operating in a world of uncertainty, where the default answer is not “I know” anymore, but rather “I don’t know.” From here, one ought to explore the boundary conditions – the upper and lower borders of said cone. Once established, one can develop scenarios along multiple dimensions, enabling leaders to play out strategies and tactics to operate in specific futures. This strengthens the strategic muscle of the organizations, enables contingency plans – all from the safety of having time and not needing to react solely in the moment.

Here’s how to start:

Identify your key uncertainties: List 3-5 factors that could dramatically change your industry

Create scenario pairs: For each uncertainty, imagine both extremes (e.g., “AI regulation becomes strict” vs. “AI remains unregulated”)

Build 2x2 matrices: Combine your top two uncertainties to create four distinct futures

Stress-test decisions: Ask “How would this strategy perform in each scenario?”

Consider how differently prepared companies were for remote work in 2020. Those who had explored “alternative futures” – where distributed teams might become necessary – adapted in weeks. Those locked into their “official future” of office-centric work struggled for months.

The paradox of our uncertain age is that those who admit “I don’t know” often see more clearly than those who claim certainty. By embracing multiple futures rather than clinging to one “official” version, leaders can achieve what Napoleon prized most: the ability to remain steady when the world goes mad. In scenario planning, as in battle, the winner is often simply the one who panics last.

@Pascal

Good post Pascal, and thanks for both the 2x2 model and the uncertainty chart.

This reminds me of a kid I saw on a skateboard the other day. He had a handwritten slogan written in black marker on a white tshirt reading: “I don’t know. Let’s figure it out.” Heroic kid! Brightened my day.

Warm wishes from Oregon. -Marshall