The Official Future Trap

Why Your Strategic Plan Might Be Your Biggest Blind Spot

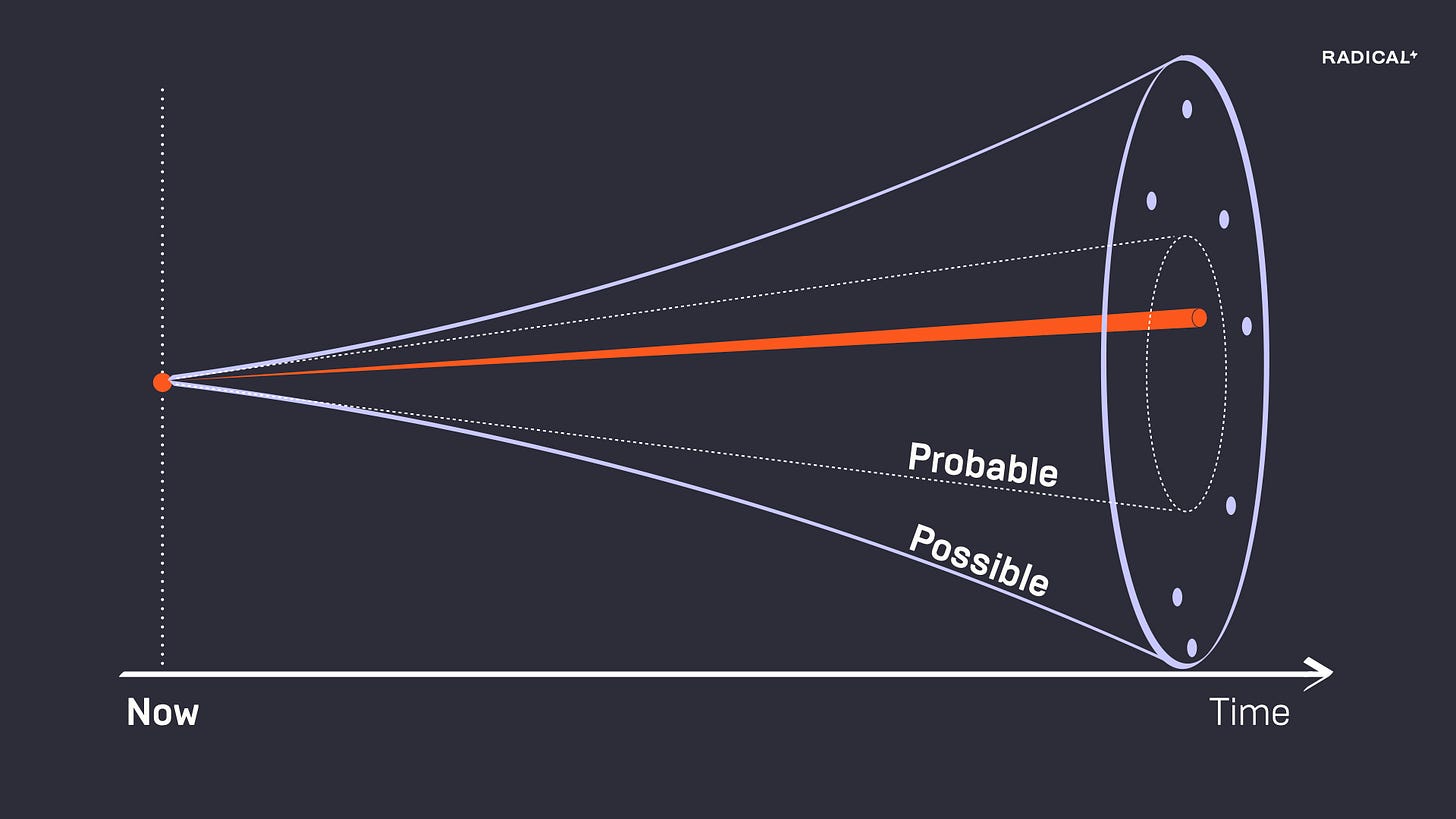

Nearly a decade ago, my dear friend and collaborator Jeffrey Rogers introduced me to the concept of the “official future”: In the academic framework of futures studies, particularly within Joseph Voros’s influential “futures cone” model, the official future is conceptualized as the projected future — “a line going straight into the future from the present time” that assumes “the future unfolding if business as usual is the norm and nothing changes.”

We regularly deploy the concept when we talk about the futures cone (aka “the cone of uncertainty”) – a reminder to think more expansively about the future, acknowledging that the future is unwritten and that the further out into the future, the wider the space of possible futures becomes. In this concept, the official future becomes a very narrow line going from the present moment into the future – it implies that there is a singular future, instead of a wide array of futures (plural).

But the official future also represents institutionally sanctioned visions that can more easily become mistaken for self-evident truths. And with that comes a whole set of challenges for leaders and their organizations. But first, let’s look at why and how we create our official future.

In our attempt to tame uncertainty, we regularly resort to a rather linear planning process – we gather information about our market, industry, customers, competitors, etc. and project from there into the future. A reasonable process on the surface. We compile this intelligence into strategic plans, resource allocation models, and multi-year roadmaps. We present these to boards and stakeholders with confidence. We build entire organizations around these projections. This feels rational. Evidence-based. Responsible even. But here’s what we’re actually doing: We’re creating what amounts to institutional comfort food – a single, linear vision of the future that makes the present feel predictable and manageable.

The official future rests on three assumptions that feel reasonable but are often catastrophically wrong:

1. Current trends will continue. We look at our market share trajectory, our customer growth, our competitive position, and we draw a line forward. Remember when Blockbuster’s official future included 10,000 stores? Their projections were based on solid data about video rental trends – trends that became irrelevant almost overnight.

2. Our competitive advantages are permanent. We identify our strengths and assume they’ll remain strengths. Nokia’s official future never included losing mobile phone dominance to a company that had never made a phone. Their engineering excellence and distribution network – advantages that seemed unassailable – became irrelevant when the smartphone redefined the game.

3. Change happens gradually. We plan for incremental shifts, not discontinuous leaps. The pandemic compressed what most organizations thought would be a 10-year digital transformation into 10 months. Gradual wasn’t an option.

Here’s where the official future becomes truly dangerous: It doesn’t just predict the future – it actively creates it. Once you’ve committed to an official future, a powerful cycle kicks in:

Official Future → Resource Allocation → Strategy → Execution → Reinforced Official Future

You allocate budget to the initiatives that support your official future. You hire people with skills relevant to that future. You build systems and infrastructure designed for that future. You create incentives that reward progress toward that future.

Each decision makes your official future more likely to occur – but it also makes you less able to adapt when reality shows up differently. This is the paradox of the official future: The more you commit to it, the more vulnerable you become.

Perhaps most dangerously, official futures crowd out alternative thinking. When your organization has an official future – embedded in strategic plans, KPIs, and incentive structures – anything that doesn’t align with it becomes “off strategy.”

Official futures create a particularly insidious problem: they make uncertainty feel manageable. We’ve all sat in strategy meetings where detailed projections for three, five, or even ten years out are presented with impressive precision. Revenue targets. Market share projections. Headcount plans. Capital allocation models.

The specificity creates confidence. “We’ve done our homework. We know where we’re going.”

But this precision is an illusion. We’re not predicting the future; we’re projecting our assumptions forward and calling it planning. The further out the projection, the more it tells you about what we believe today than what will actually happen tomorrow.

This false certainty can be more dangerous than acknowledged uncertainty. When leaders believe they know the future, they stop watching for signals that contradict it. They become deaf to weak signals and blind to emerging possibilities.

So what’s the alternative? If the official future is a trap, how do we plan for the future at all? The answer isn’t better predictions – it’s strategic optionality.

Instead of betting everything on one future, sophisticated organizations build capabilities that work across multiple futures. They don’t ask “What will the future be?” but rather “What do we need to be ready for multiple possible futures?” Let me leave you with a question Jeffrey likes to ask our clients:

What if your biggest competitive advantage comes from the future you’re NOT planning for?

@Pascal

(*) P.S.: If you haven’t listened to my recent podcast recording with Jeffrey, do so now! It is a fantastic conversation.

One useful technique to shake the recency bias and "programmed determinism" of the official future is recasting, or extending the futures cone analysis into the past.

Inevitably, the stochastic nature becomes more apparent. Whether you're doing a little of Marshall McLuhan's Back-view Mirror Analysis or even more qualitative techniques such as Delphi, Causal Layered Analysis, or the Six Pillars model.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328720301567